Responsive Teaching

On the first day of a theater camp for homeless and abused teens, I walked down the line of 40 campers and tried to teach what I had naively considered a “basic” ripple of movement. I stood next to a kid I would later learn was named Bruno, demonstrating and loudly explaining to the room how they should reach and hold each other and told the camper behind him, “now put your hand up on her shoulder like this.”

Bruno flinched at the sudden touch, and then his head snapped around, big brown eyes flitting from straight at me to the ground and back again.

Part 1: Bruno

Name pronunciation: Em-me Fan-s-ler | Pronouns: she/her

By Emmy Fansler, DWC Ambassador

On the first day of a theater camp for homeless and abused teens, I walked down the line of 40 campers and tried to teach what I had naively considered a “basic” ripple of movement. I stood next to a kid I would later learn was named Bruno, demonstrating and loudly explaining to the room how they should reach and hold each other and told the camper behind him, “now put your hand up on her shoulder like this.”

Bruno flinched at the sudden touch, and then his head snapped around, big brown eyes flitting from straight at me to the ground and back again.

“I’m a boy.”

Dead quiet. But soon after, a snicker came from across the room. And then a, “Say what?!” from somewhere down the line.

After that, the whole room laughed, aside from the 10-12 counselors and volunteers who tried to calm everyone down, a demoralized and humiliated Bruno, and me. The horror struck teaching artist that just publicly misgendered this kid whose trauma had already made it difficult to trust anyone or feel like he belonged anywhere. The activity was over and no one was willing to pick it back up, even before I’d finished teaching the entire ripple.

Talk about a humbling moment. This was not the place for the choreography I had dreamed up. I hadn’t even met these kids or considered their stories. I just assumed they’d be excited to learn what I had to teach them.

From this large group activity, the campers were split into groups and brought through my dance and movement class in 45-minute rotations. I don’t remember how many groups I worked with before Bruno’s, but I remember feeling the palpable anxiety when he came into the room— some of it (or perhaps most of it) being my own.

The goal for that day was to get to know the campers and start generating ideas for the piece they would perform at the end of two weeks. The morning had proven to me that throwing them into my preconceived routines and patterns was not going to work, so I had them stand in a circle and tell me some random things— maybe their name, pronouns, something they wanted me to know about them, something they were good at, a time they felt brave… something like that— so I could determine my next move.

Truth be told, I don’t remember any of their answers— at all. What I remember is the way Bruno nervously moved as he answered the questions— shuffling forward a few steps, then backward, over and over. His eyes everywhere but at me, hands fidgeting first in his pockets, then in his long hair, then with each other. And then when his turn was over, he stopped. I had been mesmerized, and his abrupt stop disarmed me and the “cool” I’d been trying to keep.

He noticed my staring, and I blurted out that the way he moved had sort of hypnotized me. He blushed and people stood around awkwardly, but I was inspired and his nervous movement had given me an inkling of an idea I wanted to play with. I asked him if he realized that he’d been moving, and then showed him with my body what he’d been doing. I asked the entire circle to try the forward and backward steps with me, and reluctantly they did. I added a look over the shoulder when they stepped backward, and then after a few more sets added a sigh and a single fidgeting gesture. They fell into a rhythm and suddenly I realized they were doing it without needing my continuous prompting. They listened to each other’s footfalls and coordinated their breaths organically. Watching it all come together in my head, I asked them to face the same direction instead of into the circle. The whole group trudged forward two steps, stumbled back one, brushed their hands on their pant legs, looked back, and sighed. Starting the process over and over and over.

With Bruno at the front of the formation, I asked him to make it travel, and lead it all the way across the floor. I asked a couple of them if they’d be comfortable trying it while carrying someone on their backs. I asked two more if they’d be willing to be carried. This, it seemed, was the moment they knew there was magic in the making.

The teens were engaged, excited, and enthusiastic at the way the sequence progressed from Bruno’s organic movement into the soul-stirring piece they performed for a packed house the following Friday. They partnered. They rippled. They rolled and reached and leapt and lifted Bruno up to the sky with a blue cyc and remnants of broken furniture hanging from the flies. They started with diagonal trudging and ended with eyes up, chests open, backs arched, hands on shoulders, showing support and care for each other in front of hundreds of strangers. Not one of them having taken a dance class before camp, but all of them KNOWING they had just moved the hearts of every single person witnessing them. There were no pirouettes, no high kicks, no tricks of any kind… maybe four pointed feet, total. Just a bunch of beautiful teens with a story to tell— one that began unfolding out of the anxious movement and emotional responses of one brave and vulnerable student named Bruno.

This was a formative experience, not only for the kids who found a platform to share their stories of resilience, but for me as a teacher and choreographer. It forever shifted the way I choreograph and opened my eyes to the beauty of teaching the non-traditional dancer. You don’t need years of training, the perfect body, or endless financial resources to be a dancer and tell your story through movement. You need a body and space. And… you don’t need dancers with a life of devoted ballet technique, marley floor, and perfectly performed etiquette to choreograph and create a life-changing piece— you need the willingness to see the humans in front of you, an openness to what they’re sharing with you just by existing, curiosity, creativity, and love for the incredible work you get to do.

Disclaimer

All content found on the Dancewear Center Website, Instagram, Facebook, Pinterest, and all other relevant social media platforms including: text, images, audio, or other formats were created for informational purposes only. Offerings for continuing education credits are clearly identified and the appropriate target audience is identified. The Content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this Website.

If you think you may have a medical emergency, call your doctor, go to the emergency department, or call 911 immediately. Dancewear Center does not recommend or endorse any specific tests, physicians, products, procedures, opinions, or other information that may be mentioned on dancewearcenter.net. Reliance on any information provided by dancewearcenter.net, Dancewear Center employees, contracted writers, or medical professionals presenting content for publication to Dancewear Center is solely at your own risk.

Links to educational content not created by Dancewear Center are taken at your own risk. Dancewear Center is not responsible for the claims of external websites and education companies.

Providing Opportunity Through Community Classes

Moving forward, Lex wishes for dance teachers to communicate with one another more. There’s a strong feeling of competition that runs across the dance industry, causing teachers, dancers, and other industry professionals to retreat to their silos. Lex points out that it’s hard for dancers and teachers to grow when they feel like they’re being judged. “There’s this weird expectation that if you’re a teacher, you have to be good at everything and that’s just not realistic,” Lex says. “So it’s hard to find a space in your community as a teacher, where you feel like you can work on yourself free of judgment.” She says that it would be great for Drop Zone to host events where teachers can come into conversation with one another about their unique struggles.

Drop Zone’s Lex Ramirez on Offering Equitable Access to Dance

By Madison Huizinga, DWC Blog Editor

Photo by Val Gonzales

The world of dance is replete with gatekeepers, holding many people interested in learning more about the art form and cultivating community back from succeeding. There’s a great need for community spaces where people of all social identities can show up free of judgment and feel like they’re a part of something bigger than themselves. Thanks to Lex Ramirez, spaces like that are coming to fruition. Drop Zone is Lex’s latest creation: a creative dance hub featuring “classes, events, and groups centering artists from marginalized communities.”

Lex was first exposed to dance through Mexican folk dancing around age eight. She was also a part of a Catholic youth cheerleading organization. In school, she found a community of girls who loved hip hop, like her. The group got together outside of school to dance together and teach one another. In college, Lex’s passion for hip hop persevered, as she joined a hip hop dance team.

She moved from her hometown of Oakland to Seattle when she received a fellowship in multicultural education, involving a program interested in getting more people of color involved in outdoor education. “I knew it was a good opportunity to learn some skills about teaching in an accessible way to BIPOC youth,” Lex says. She had intended to only move to Seattle for a year to do the fellowship. However, one day, Lex decided to stop into the dance studio she always passed on her way to work. She took a class and loved it, eventually teaching several classes herself. “It was like the universe being like ‘no, stay here,’” Lex says.

“I never did studio dance [as a kid],” Lex shares. “I think that’s an important part of my journey.” She shares that the spaces she danced in growing up were always extremely welcoming. While many dance studios focus on catering to pre-professional dancers, Lex felt like the dance communities she’s been a part of welcomed all dancers, from those who wanted to pursue it as a career to those who saw it as a passionate, recreational outlet.

However, after struggling with a traumatic experience within the dance community, Lex realized that no dancer should feel unwelcome and put down in the ways she felt. Having worked in dance administration, taught, and danced as an artist herself, she decided to bring all of her skills together to create a safe and equitable hub for dancers in the Seattle area.

Lex currently teaches at Dance Underground and is shocked at how many people are unaware of the space. “I have a lot of students and I wanted a way for instructors to be connected to my student base, but also for my students to be exposed to them,” Lex says. “I also wanted to uplift artists from marginalized communities...I wanted to create a space where both teachers and students could grow.” Thus, Drop Zone was born.

Currently, Drop Zone offers community classes for the public in styles like hip hop, breaking, hustle, contemporary, and sensual floor work, as well as a dance crew called Drop Squad, open for hip hop dancers of all experience levels. The community classes are on a sliding-scale cost, from $5-20. Funds go towards supporting the instructors. Looking forward, Lex hopes to host events through Drop Zone that foster community, as well as bridge the gap between dancers, musicians, photographers, videographers, and other artists. She looks forward to organizing more dance projects that feed dancers and instructors creatively.

Moving forward, Lex wishes for dance teachers to communicate with one another more. There’s a strong feeling of competition that runs across the dance industry, causing teachers, dancers, and other industry professionals to retreat to their silos. Lex points out that it’s hard for dancers and teachers to grow when they feel like they’re being judged. “There’s this weird expectation that if you’re a teacher, you have to be good at everything and that’s just not realistic,” Lex says. “So it’s hard to find a space in your community as a teacher, where you feel like you can work on yourself free of judgment.” She says that it would be great for Drop Zone to host events where teachers can come into conversation with one another about their unique struggles. “I think it’s really important to collaborate, so that we can all differentiate ourselves and what we offer.” There should be a space for every teacher and every dancer to exist in the community.

Be sure to follow Lex and Drop Zone on Instagram to hear about upcoming events.

Disclaimer

All content found on the Dancewear Center Website, Instagram, Facebook, Pinterest, and all other relevant social media platforms including: text, images, audio, or other formats were created for informational purposes only. Offerings for continuing education credits are clearly identified and the appropriate target audience is identified. The Content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this Website.

If you think you may have a medical emergency, call your doctor, go to the emergency department, or call 911 immediately. Dancewear Center does not recommend or endorse any specific tests, physicians, products, procedures, opinions, or other information that may be mentioned on dancewearcenter.net. Reliance on any information provided by dancewearcenter.net, Dancewear Center employees, contracted writers, or medical professionals presenting content for publication to Dancewear Center is solely at your own risk.

Links to educational content not created by Dancewear Center are taken at your own risk. Dancewear Center is not responsible for the claims of external websites and education companies.

A Local Dancer On Storytelling and Building Community Through Dance

Alex Ung shares that when people ask about his nationality, he often uses an umbrella term, like sharing that his family is from Laos, rather than diving deeper into his more specific tribal culture of the Tai Dam. “It was just easier,” Alex says. “Immigration Stories” provided Alex with an opportunity to share more about his culture, in an effort to “not let it disappear into history books” and simultaneously help write history. “We’re a small tribal culture that not a whole lot of people know about and so I wanted to bring that to light,” he says of the Tai Dam people.

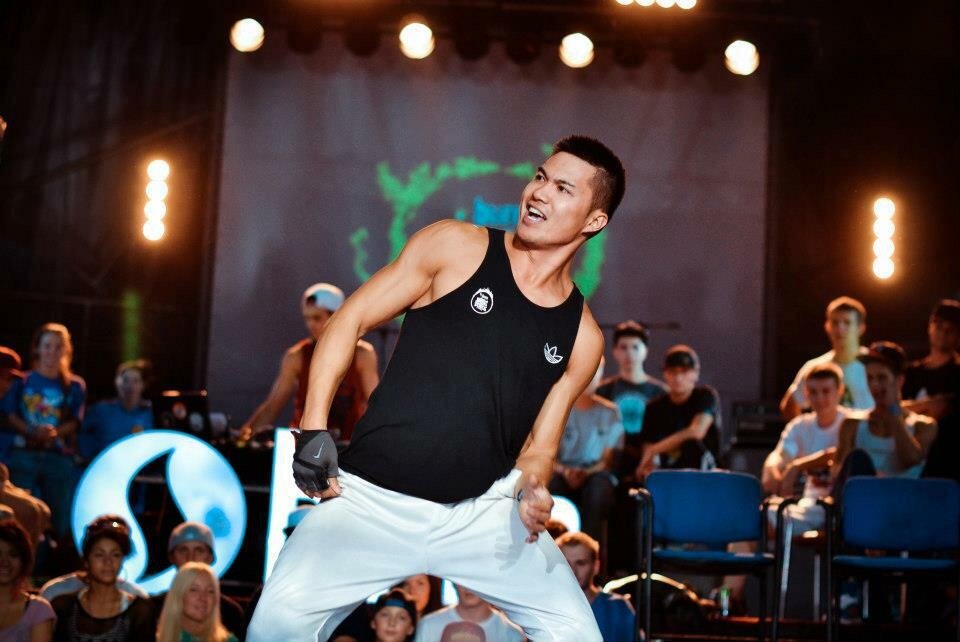

Alex Ung on Cultural Representation and the Guild’s Plans for 2022

By Madison Huizinga, DWC Blog Editor

Photo by Karya Schanilec

Art has the power to move people in ways unimaginable. Through creating and performing dance works, choreographers and dancers have the power to express their emotions and connect to their cultural backgrounds and local communities. Alex Ung of the Guild Dance Company opens up about sharing his familial and cultural background through dance, bolstering community, and the Guild’s plans for 2022. Be sure to catch the Guild’s show “El Camino” and their performance at the Seattle International Dance Festival in June.

Alex was born and raised in Iowa, where he began dancing in high school in the show choir and competition scene. But Alex shares that his dance career didn’t start until college when he began working with the hip hop club at Iowa State University. “I think that’s where it really hit me that I really love to dance,” he shares.

When Alex moved to the Seattle area, he began teaching hip hop at a dance studio on Bainbridge Island, where he worked for over a decade. He eventually broadened his scope into jazz, contemporary jazz, and contemporary ballet styles, and also began directing the competition dance team. Alex has worked with other dance studios and companies in the Seattle area, including Jeroba Dance.

Alex says that dance has stuck with him largely because he has a tough time expressing his emotions and thoughts through words. “I feel like I can do it a bit better with my body [and] with my movement style,” he says of emoting. Having earned a degree in engineering, Alex also shares that he has an appreciation for the aesthetics of lines and shapes in dance and witnessing the physical challenges that the body can endure. He loves the feeling of doing something physical that he didn’t think he could do and surprising himself.

In 2018, Alex founded the Guild Dance Company after taking a break from teaching. He shares that he had missed creating dance and wanted to jump back into the choreographic world to tell his own stories in his own style, as well as learn from other dancers. “I thought building my own dance company would be a good way to do that,” Alex says, sharing that the Guild has become a place for dancers to build each other up.

“For me, the Guild is about the community and learning and experiencing each other,” Alex says. He loves being able to express himself and be vulnerable alongside the rest of the company dancers.

In 2019, the Guild Dance Company performed “Immigration Stories,” a show inspired by Alex’s family’s experience immigrating to the United States from Laos. Following high school, Alex and many of his relatives that were his age felt like their traditional culture was dying, as many of them were not making efforts to learn their family’s language or carry out traditional cultural activities. “It felt sad to me,” Alex shares. “I wanted to create a work that could help people understand where my family was coming from, where we came from in the past, and where we are right now.”

Alex shares that when people ask about his nationality, he often uses an umbrella term, like sharing that his family is from Laos, rather than diving deeper into his more specific tribal culture of the Tai Dam. “It was just easier,” Alex says. “Immigration Stories” provided Alex with an opportunity to share more about his culture, in an effort to “not let it disappear into history books” and simultaneously help write history. “We’re a small tribal culture that not a whole lot of people know about and so I wanted to bring that to light,” he says of the Tai Dam people.

Through interviewing his family and others, Alex realized how fortunate he is to be doing what he loves as a result of the sacrifices and risks his family made. He also learned that people from different cultures shared similar immigration experiences, which sparked inspiration. He found it so meaningful to find that people aren’t alone in their challenges and that community can be an invaluable form of support.

Amid the rise of hate crimes against Asian Americans during the COVID-19 pandemic, Alex reflected on the racism he and his family had experienced in Seattle and elsewhere and felt angry. “I wanted to express my frustration and my experience with what was going on,” he says. So Alex brought together a group of dancers of color to create a video surrounding the theme of “Stop the Hate, Stop the Injustice.” An important co-producer in the process was local artist Alicia Mullikin, a first-generation Mexican American dance artist, educator, and community organizer. Alex shares that the project was a way for community members from various cultural backgrounds to come together and express their feelings of frustration and hurt regarding the rising hate crimes and common struggles they experienced.

Photo by Stuart Murtland

In the dance community, Alex hopes to see more dancers supporting one another, specifically by attending one another’s shows. “We’re all in the same bubble,” Alex shares, pointing to how Seattle-based dancers all face similar challenges, particularly finding funding to create work.

Moving into the next year, the Guild is planning to put on “El Camino,” a music and dance production made in collaboration with the Tudor Choir inspired by the pilgrims that traveled on the iconic Camino de Santiago. Alex drew inspiration for the production after walking on the trail himself, and undergoing what he describes as a “life-changing experience.” He was enamored by the people he met and the towns he passed through, learning about the different intentions of people embarking on the journey. Stay tuned to the Guild Dance Company’s website for more information about show dates!

The Guild Dance Company also plans to perform in the 2022 Seattle International Dance Festival this June, tickets are available here.

Disclaimer

All content found on the Dancewear Center Website, Instagram, Facebook, Pinterest, and all other relevant social media platforms including: text, images, audio, or other formats were created for informational purposes only. Offerings for continuing education credits are clearly identified and the appropriate target audience is identified. The Content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this Website.

If you think you may have a medical emergency, call your doctor, go to the emergency department, or call 911 immediately. Dancewear Center does not recommend or endorse any specific tests, physicians, products, procedures, opinions, or other information that may be mentioned on dancewearcenter.net. Reliance on any information provided by dancewearcenter.net, Dancewear Center employees, contracted writers, or medical professionals presenting content for publication to Dancewear Center is solely at your own risk.

Links to educational content not created by Dancewear Center are taken at your own risk. Dancewear Center is not responsible for the claims of external websites and education companies.

Dr. Miguel Almario on Holistic Teaching and PT Care

“I would like to see a lot more empathy towards the culture and the people that created the dance,” Miguel says of a change he hopes to see made in the larger dance industry. He shares that many of the people who created dance genres like hip hop and breaking are still alive and accessible to dancers, yet their contributions can get drowned out. More focused on physicality, Miguel also hopes to see more dancers treating and training their bodies like the athletes that they are so that they can keep dancing for as long as they can. “You’ve got to put that work in so that you can keep going,” he shares.

On Offering Cultural Competency and Wellness Services

By Madison Huizinga, DWC Blog Editor

Photo by Adam Gatdula

Having a full appreciation and understanding of the history and mechanics of dance requires more than just time in the studio. Dancers like Dr. Miguel Almario are providing community members with the cultural context behind their movements and access to compassionate and individualized physical therapy services. Read on to learn more about Miguel’s dance journey in the freestyle and commercial space, teaching programs at The Arete Project, and PT services at MovementX.

Miguel started exploring breaking his junior year of high school when his younger brother encouraged him to give it a try. He joined a local dance troupe called Culture Shock DC, a non-profit dance organization in the Washington DC area aimed at community outreach. Miguel’s passion for dance grew immensely. He says that one of the things he loves most about dance is that one person’s artistic expression can differ so much from another’s. “I have the freedom to find my voice and my style of movement,” Miguel shares.

He later ended up competing on the TV show America’s Best Dance Crew on MTV in Los Angeles, California. “That was a time where I was like ‘I can make something of this,’” Miguel says of the turning point in his career. After competing on TV, Miguel shares he started focusing on dance in a more professional capacity, as prior to the show, he hadn’t experienced any “formal” training. Growing up, outside of Culture Shock DC, Miguel practiced dance in his friends’ basement and in his school’s cafeteria, often ordering VHS tapes of competitions to study and draw inspiration from.

After some time, Miguel decided to take a break from dance and returned home to DC from LA. He shares that this was a time in his life when he deeply pondered what kind of life he was going to lead. “I always knew I wanted to be working with people,” Miguel says. Eventually, he landed on pursuing physical therapy, sharing that both of his parents were physicians which greatly influenced him. He thought PT could provide him with the opportunity to bridge the worlds of dance and physical medicine.

While in PT school, Miguel danced with a dance team in Boston, Massachusetts, where he underwent rigorous training. After graduating from PT school, he moved back to Los Angeles to work as a physical therapist and dancer.

Photo by Adam Gatdula

Following his experience in the traditional physical therapy clinic setting, Miguel realized he was interested in working in a role that allowed him to make stronger, more intimate connections with his clients. That’s when he got connected with MovementX, a physical therapy provider that offers in-person and virtual treatment that is adaptable to clients’ varied lifestyles.

“I work with a lot of dancers,” Miguel says of his PT work at MovementX, sharing that he serves all kinds of clients, including those recovering from minor or major injuries, those looking to improve their ability to move or perform, or those who feel generally physically limited in one way or another.

Miguel shares that his dance experience has been unique, as he has trained in more community-oriented, freestyle, breaking spaces, and has had heavy exposure to the more commercial world as well. Miguel’s wife Niecey Almario is also a dancer, teacher, and choreographer. Today, Niecey and Miguel Almario teach a variety of courses together in Seattle through The Arete Project. Miguel shares that he and his wife collectively offer a holistic dance experience, informing people of the cultural context behind movements and how certain techniques can apply to different professional settings, like on a dance team or in a music video.

Photo by Adam Gatdula

Honoring the cultural roots of different styles of movement is of the utmost importance to Miguel. For example, he shares that hip hop and street dance have roots in Black American communities and that it’s important for people to know this to understand and appreciate the art form more fully. Miguel shares that learning the history behind dance styles like hip hop has made him realize that this art form he partakes in is much bigger than him as an individual.

“I would like to see a lot more empathy towards the culture and the people that created the dance,” Miguel says of a change he hopes to see made in the larger dance industry. He shares that many of the people who created dance genres like hip hop and breaking are still alive and accessible to dancers, yet their contributions can get drowned out. More focused on physicality, Miguel also hopes to see more dancers treating and training their bodies like the athletes that they are so that they can keep dancing for as long as they can. “You’ve got to put that work in so that you can keep going,” he shares.

Disclaimer

All content found on the Dancewear Center Website, Instagram, Facebook, Pinterest, and all other relevant social media platforms including: text, images, audio, or other formats were created for informational purposes only. Offerings for continuing education credits are clearly identified and the appropriate target audience is identified. The Content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this Website.

If you think you may have a medical emergency, call your doctor, go to the emergency department, or call 911 immediately. Dancewear Center does not recommend or endorse any specific tests, physicians, products, procedures, opinions, or other information that may be mentioned on dancewearcenter.net. Reliance on any information provided by dancewearcenter.net, Dancewear Center employees, contracted writers, or medical professionals presenting content for publication to Dancewear Center is solely at your own risk.

Links to educational content not created by Dancewear Center are taken at your own risk. Dancewear Center is not responsible for the claims of external websites and education companies.

A Non-Profit’s Vision For Equitable Dance Access

From her numerous years of experience in the industry, Kari Hovde knows that finding and securing opportunities for talented young dancers can be challenging. Due to numerous circumstances, opportunities for personal and professional development in the industry can be out of reach for even the most technically proficient young dancers. That’s why Kari founded The Backstage Foundation, a non-profit organization that funds opportunities for young dancers to build their talent and character via scholarships. Read on to learn more about Kari’s background, the story behind The Backstage Foundation, and the upcoming "In the Spotlight” benefit show on May 20, 2022, at 7:00 PM at the Kirkland Performance Center.

Kari Hovde on Offering Opportunities Through The Backstage Foundation

By Madison Huizinga, DWC Blog Editor

Photo by TrueONE Group

From her numerous years of experience in the industry, Kari Hovde knows that finding and securing opportunities for talented young dancers can be challenging. Due to numerous circumstances, opportunities for personal and professional development in the industry can be out of reach for even the most technically proficient young dancers. That’s why Kari founded The Backstage Foundation, a non-profit organization that funds opportunities for young dancers to build their talent and character via scholarships. Read on to learn more about Kari’s background, the story behind The Backstage Foundation, and the upcoming "In the Spotlight” benefit show on May 20, 2022, at 7:00 PM at the Kirkland Performance Center.

Kari has been a part of the dance world her whole life and what she’s loved most about it is the community. “Dance is family,” Kari says, sharing that the bond people make with those at their studio is incredibly valuable. The positive energy, excitement, encouragement, and support that comes from dancing is irreplaceable, and for many dancers, their dance family may be their only support system.

Over the course of her journey, Kari has witnessed the high expenses of dance and the inequitable opportunities available to children from families of different socioeconomic statuses. “I have always wanted to be able to provide talented young dancers with [opportunities],” she says, sharing that she brainstormed ideas about how to make experiences like traveling to intensives and conventions more accessible. Kari ultimately landed on a needs-based scholarship, consisting of a written application, a talent video, and a story video, in which applicants explain their background, their desire for the scholarship, and their passion for dance.

“Dance brings so much more to their lives than just the talent and the technique,” Kari explains the value of dance in a young person’s life. “It brings values that [dancers can] carry with them through the rest of life to apply towards all the things that they do, from career to relationships.” Kari and the rest of the team at The Backstage Foundation believe that dance brings forth community, dedication, great work ethic, problem-solving, and numerous other skills that are instrumental for personal and professional development.

Photo by Leslie Cheng

The core values of The Backstage Foundation are experience, community, and opportunity, and that certainly comes through in what the organization offers to dancers. Kari says she drew inspiration for the project after coaching a talented high school hip hop team and realizing the dancers in the group had few opportunities outside of school to showcase their skills. She wanted the team to be able to take professional-level classes, travel to showcase their skills and have the opportunities dancers in studios often have.

In general, Kari would love to see more opportunities for dancers on a local level, including access to spaces like dance conventions, which can help facilitate transitions from small dance studios to more professional work. She would love community members to start thinking about ways to bridge the gap between that safe studio space to the new, adventurous, professional terrain, in a way that keeps dancers secure and successful. Kari thinks mentorship programs and workshops could assist dancers with that transition and allow them to see if the professional world is for them.

On a more global level, Kari hopes to see a bit more safety and security in the dance industry. She believes it’s important that young dancers have people in their lives that they can trust, including agents and talent managers, that can guide them with the professional decisions they choose to make. The last thing Kari wants is for young dancers to be taken advantage of in any capacity. Professionals in the dance industry have the power to gather the right kind of leadership and guidance for young people, and Kari is looking forward to seeing what that can look like.

Photo by TrueONE Group

The Backstage Foundation is thrilled to be having its annual benefit show “In the Spotlight” on May 20, 2022, at 7:00 PM at the Kirkland Performance Center. Attendees can expect to watch 75 performers dance in over 35 routines, featuring Amity Addrisi from King 5’s New Day Northwest as the emcee and choreographer Tina Landon as the guest speaker of the event. “We’re quite excited for that event!” Kari shares. “It’s going to be very fun with lots of inspiration, entertainment, and heartfelt stories.” Tickets are selling quickly, so be sure to get yours as soon as possible! You can secure your ticket here.

The Backstage Foundation’s first round of scholarship opportunities will open in June, so dancers are encouraged to keep an eye out for that on the organization’s website. “The selection committee will be very excited to see everyone’s submissions!” Kari shares.

Finding Your “Why”: Jerome Aparis on How Breaking Feeds His Soul

At the end of AAPI month, Jerome Aparis shared his journey to becoming a co-founder and current member of the world-renowned breaking crew, Massive Monkees. From studying VHS tapes of breakers in sixth grade to creating an internationally acclaimed crew and achieving global accolades, Jerome recounts how the values of hard work and creativity from his cultural heritage have fueled his drive for success and purpose.

Trigger Warning: Trauma, Sexual Assault

By Isabel Reck & Madison Huizinga. DWC Blog Contributors

At the end of AAPI month, Jerome Aparis shared his journey on becoming a co-founder and current member of the world-renowned breaking crew, Massive Monkees. From studying VHS tapes of breakers in sixth grade to creating an internationally acclaimed crew and achieving global accolades, Jerome recounts how the values of hard work and creativity from his cultural heritage have fueled his drive for success and purpose.

Jerome began his dance journey around age 12 by watching videos of breakdancing crews from Seattle. At the time, this art form was predominantly underground and information about it traveled almost exclusively through word of mouth. A movie that was particularly influential for him growing up was Beat Street, a film showcasing the NYC hip hop culture of breaking, MCing, DJing, and graffiti art in the early 1980s. Jerome had never seen dancing like what he witnessed in Beat Street and various other videos. He was immediately pulled in.

When Jerome was a kid, most people his age learned breaking at local community centers, which were relatively informal and open to the public. The community centers were usually packed to the brim, and Jerome recalls sometimes only getting a couple of minutes of one-on-one time with his instructor. Despite this challenge, the attitude he adopted was about “maximizing what [he] learned.” Jerome recalls often not understanding certain steps the first couple of times he practiced them at the center. He would go home and rehearse in his kitchen for hours so he could go back to the community center and show off his improvement. Being able to advance through practice and showcase his progress made him confident that he was worthy of his instructor’s time and worthy of being a student.

This attitude and commitment to breaking led Jerome to make an impressive and successful career for himself. He co-founded the world-famous breaking crew, Massive Monkees in 1996. This group and its members have shared the stage with the likes of Macklemore, Missy Elliot, Jay-Z, and Alicia Keys. Massive Monkees also finished third overall in MTV’s America’s Best Dance Crew in 2009 and won the 2004 B-Boy World Championship in London and 2012 R-16 World Championship in Seoul, Korea. Jerome later won ten national titles with the crew Massive Monkees. Today, Jerome coaches students at the Massive Monkees Studio: The Beacon, and at Cornerstone Studio with his wife, Lea Aparis, who’s also the studio’s owner.

“When you don’t have much, creativity is huge.”

Jerome shares that his Filipino heritage has largely shaped the individual and performer he is today. Jerome was born in the Philippines and moved to the United States at age three. When he returned to the Philippines at age 15, he remembers seeing how hard the people from his hometown worked, including his own family. He recalls kids in his hometown, outside of the city, walking miles just to get water and attend school. Community members who were lacking the resources that urban-dwellers possessed needed to act creatively to work around the challenges they faced. These values—hard work and creativity—Jerome recognized in the Philippines, pushed him to achieve the accomplishments he has today. “Mak[ing] something out of nothing” is a theme that he has carried with him throughout his journey. “When you don’t have much, creativity is huge,” he explains.

One instance in the Philippines that was particularly inspiring to Jerome occurred when he visited his sister at work. Jerome’s sister performs government work in the Philippines, working at a safe house for young girls who have been victimized by sex trafficking. The leads at the safe house asked Jerome if he was interested in speaking with the girls and perhaps teaching a workshop. They told him these girls were scared and felt like they didn't have a voice. Knowing that these young girls had developed significant fears, particularly of outsider men, Jerome knew “it [was] time to step up to the plate.” What occurred at the safe house was the “most life-changing 60 minutes of [his] life.”

At the beginning of the workshop, these girls, ages 5-17, were incredibly quiet. At first, the session centered on talking and why using their voices is important. Then, Jerome transitioned into teaching them choreography that communicated their strength and power. By the end of the workshop, he describes how the girls were “just going for it” and how their energy had completely changed. Later, they all sat in a circle and each girl opened up about her story. Jerome carries these stories with him today. “It’s way bigger than just winning a trophy,” he shares.

To be a successful professional dancer, Jerome makes it clear that a performer must know their “why.” Why do you do what you do? Jerome explains that in dance it’s easy to be driven to succeed to simply fuel your ego. You merely dance for the winning, the fame, and the glory. But beyond expanding your ego, your “why” must be fueled by the need to make yourself feel genuinely confident and feed your soul. Jerome’s experience teaching in the Philippines did just this. Helping kids “understand that there is so much greatness in them” is what coaching has become to him and is “one of his biggest passions.”

Jerome’s biggest takeaway from his career is simple: “find your why.” Once you know this everything else will follow.

“Find your why, once you know this everything else will follow.”

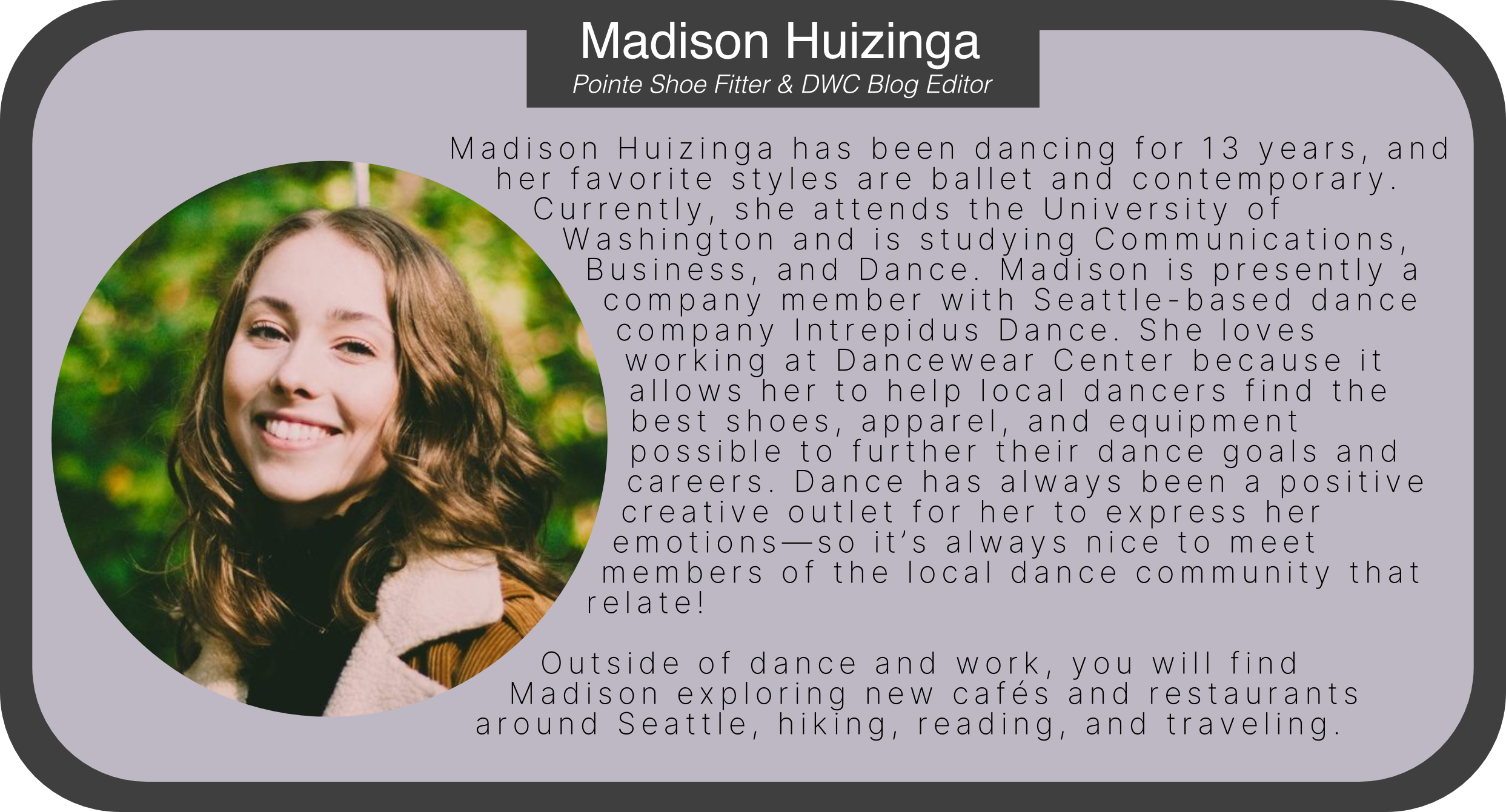

Madison Huizinga has been dancing for 13 years, and her favorite styles are ballet and contemporary. Currently, she attends the University of Washington and is studying Communications, Business, and Dance. Madison is presently a company member with Seattle-based dance company Intrepidus Dance. She loves working at Dancewear Center because it allows her to help local dancers find the best shoes, apparel, and equipment possible to further their dance goals and careers. Dance has always been a positive creative outlet for her to express her emotions—so it’s always nice to meet members of the local dance community that relate!

Outside of dance and work, you will find Madison exploring new cafés and restaurants around Seattle, hiking, reading, and traveling.

Isabel Reck has been dancing since she was 12; the majority of her training being at Cornerstone Studio. She has trained in ballet, contemporary, lyrical, jazz, hip-hop, tap, breakdancing, and aerial silks, although contemporary has always been her go-to. Her favorite thing about working with DWC is being able to explore a new side of dance she never thought she would be a part of.

The Division of Self, the Division of Identity

How we are defined is important. It helps tell the world our values, our morals, and our interests. But who makes that definition? Do we set the parameters ourselves by means that we dictate? Or is it determined by our background, heritage, and childhood?

As with most things in life, I suspect it’s a little of everything. There are factors we cannot control that play insurmountably in how we are viewed, including skin color, eye shape, and our parent’s socio-economic status. But there are other things that ebb and flow with our own desires like our morals, our interests, and the places we go. And then there are things that just happen, random events that you may not even realize are significant until ten years later when you look back at your life and realize that one seemingly meaningless decision, event, or person, changes the trajectory of your whole life.

Trigger Warning: Racial Slurs Used in Context, Mental Health

By Ethan Rome, DWC Director of Marketing

How we are defined is important. It helps tell the world our values, our morals, and our interests. But who makes that definition? Do we set the parameters ourselves by means that we dictate? Or is it determined by our background, heritage, and childhood?

As with most things in life, I suspect it’s a little of everything. There are factors we cannot control that play insurmountably in how we are viewed, including skin color, eye shape, and our parent’s socio-economic status. But there are other things that ebb and flow with our own desires like our morals, our interests, and the places we go. And then there are things that just happen, random events that you may not even realize are significant until ten years later when you look back at your life and realize that one seemingly meaningless decision, event, or person, changes the trajectory of your whole life.

Looking back at these things in my own life, it’s easy to point out why I made certain decisions. However, in those moments, there is no way I could have known why. As most people do, I make decisions in the present based on factors that I think I have set. But ten years from now, I’m certain I will realize that it could not have been any other way. We could go on for days dissecting every detail, but today I want to focus on a particular one. In light of Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, I want to speak about one of the most prominent factors that has created a division in my own self.

I am half Korean and half Scandinavian. Which in my life has meant I am not enough of anything to anyone. Everyone sees me as an “other.” I cannot count the number of times a White person has asked me, “so are you Chinese or something?” Or the number of times an Asian person simply won’t speak to me until I’m able to gently assert my own Asian-ness (by somehow slipping it into the dead conversation, or saying “thank you” in Korean). Or the number of times someone of any race has said “so what are you?” I have been called both “chink-eyes” and “the white boy.” Growing up, I can only remember having one mixed-race friend and recall often wishing I could “just be normal.” There was a period of my life when I tried to pass (as singularly White). People would ask me, “So what are you?” I would reply “I’m normal, you know White.” I can confidently say now that White does not equal “normal.” There is nothing wrong with being White, but we can’t allow it to be the standard to which all other races must be compared. You are not irregular or weird because of your skin tone, culture, or ethnicity.

Everywhere I go, I feel left out or pushed aside by the people that I feel look like me or think like me. Feelings of dismissal and ostracization can lead to serious disorders. Studies have shown that people of mixed race “were the most likely to screen positive or at-risk for alcohol/substance use disorders, anxiety, depression, eating disorders, and psychosis” (Imposter Syndrome in Multiracial Individuals). Because of this, I have always longed for a community that I felt I belonged to, but that also one that wanted me.

Due to this longing for community I have always tried new clubs, sports and activities. When I went to college, I was still searching for that sense of belonging. Therefore, I searched through the college club directory and decided to try breaking (or breakdancing). The intensity and uniqueness of breaking was reminiscent of watching Bruce Lee, one of the few male Asian icons in American culture. I saw something of myself in those bboys. Thus began my dance journey.

The breakers, and breaking in general, were very welcoming. They themselves came from all kinds of backgrounds, some grew up breaking, some only started a year ago, most were self-taught, all of them were glad to teach what they knew and have a conversation. This was likely aided by the fact that they were all so different from each other, dancers were Asian, Pacific Islander, Middle Eastern, White, Black, and Hispanic. It was possibly the most diverse group on campus in terms of race/ethnicity. During this time, my feelings of unease or dismissal subsided, it does not matter what you look like when everyone looks different from the person standing next to them. However, being mixed raced is a unique beast that may slumber, but never dies.

During my time as a bboy, I also started to take classes in the Dance Department, ballet and modern specifically. Entering into the Dance Department came with the shock of the technical details of classical dance, as well as the fact that I was pretty much the only Asian person in the department, and one of the few people of color. I was suddenly back to being an “other.” Dancers are largely open-minded and accepting people. But even well-intentioned people might not notice their microaggressions, or don’t understand why calling me a “ninja” is maybe not the compliment they think it is (ninja are Japanese, I’m Korean, ninja were also often viewed as individuals without honor, assassins sent to do the dirty work and were shunned for completing the tasks given to them). My newfound passion in modern created the next division of my identity. Was I a breaker, or was I a modern dancer? For many reasons I chose to finish my degree in dance, and attempt a career as a “modern dancer.”

Moving to Seattle was a significant change in many ways, and it too was just a random event that happened to happen. Living in Seattle opened the door of contemporary dance. Contemporary has its own confusing and mixed background. Did it come from the lyrical/contemporary world? Did it come from the contemporary ballet world? Is it neither? Is it both? Perhaps it's because of this ambiguity that I became so enamored with it. It is almost a blank canvas, to be determined and designed by me. It is a place where I can express myself fully. I can utilize my classical training, I can incorporate my breaking origin. There is no one to tell me what I am or can do as a contemporary artist. I can use my art to express any idea I want such as my Korean heritage.

This piece was created in response to the recent outbreak of anti-Asian hatred

After moving here I also started to feel that I wasn’t quite as much of an outsider. They are still relatively few, but I have met more Hapa (a Hawaiian word meaning “half,” it has been co-opted by the half/mixed-Asian community and has its own controversy behind it) here than in the rest of my life combined. It has been wonderful to connect with others like me and to learn that I was not alone. I do not think the answer to solving this problem is simply to have more mixed raced babies, in fact, that too can be problematic; “We could have such beautiful babies'' is a terrible thing to say, reduces someone to their race, a singular part of their identity, and tokenizes certain races. It’s another example of a micro-aggression and how people often don’t understand that their “compliment” is actually quite demeaning.

So what can we do?

You can help by taking a moment to put yourself in someone else’s shoes. Your compliment may be an insult to someone else (one man’s trash…). Do they understand that you meant to compliment them? Do you understand the cultural context you might be implying? Allow others to be themselves, accept them for who they are and let them demonstrate to you how they wish to be treated. Authentic representation also tells people they matter and shows them they are not alone. If you are multi-racial, then be yourself! If it is a part of you, don’t try to hide it, it very likely won’t work anyway.

If you feel you are an “other” I encourage you to take a deep breath, you are not alone. It may take time, it may be painful, but you can find ways to connect if you keep pushing yourself. Remove yourself from your ego, from notions of who you or other people think you need to be or should accomplish. Do not be afraid to enjoy something simply because other people look down on you for it, they probably just don’t understand it well enough. Your community might not look the way you envision it now, in fact, it is very likely to look entirely different, but it is out there. Alan Watts once said, “So don't worry too much, somebody's interested in everything. And anything you can be interested in, you'll find others will.”

Looking back at it now I see that there was really no other way, I was never going to fully be a bboy, I was never going to fully be a modern dancer; I will never be fully Asian nor fully White, I always have and always will be split. But that is not necessarily a bad thing. I am more empathic, more understanding, and more accepting because of it. And I am a significantly more unique artist because of it. I learned to see the strengths of my divisions. My only regret was how long I tried to hide and failed to see how my uniqueness can define my positive attributes as well as the negatives.

Looking back at it now I am grateful for my own confusing and mixed background.

Caring for Ourselves as Dancers of Color

As a chunky Asian baby in a leotard, I had no idea yet how precious or valuable I was when I started in ballet. Instead, I only saw that I was clearly not cut from the same cloth as elegant princesses and swans whose dancing I admired. The chance to don yellowface in the Chinese variation during "The Nutcracker," or to be a kowtowing, shuffling child in "The King and I" in the school play felt like places I was welcome to exist—to shine—as a child who dreamed of being onstage.

By Gabrielle Nomura Gainor

Gabrielle Kazuko Nomura Gainor (she/her) is an artist, writer, and Asian American community activist. In addition to working in communications/public engagement at Seattle Opera, she's received grants from Seattle's Office of Arts & Culture and the Washington State Arts Commission. In 2021, Gabrielle has been proud to serve as a mentor and Teaching Artist with TeenTix.

Counterclockwise from top left: Gabrielle Nomura Gainor, surrounded by Dominique See, Alyssa Fung, Siena Dumas, and Hailey Burt in Farewell Shikata ga nai; Joseph Lambert photo. Christopher Montoya en pointe. Vivian Little smiles. Robert Moore jumps; Tracey Wong photo.

May was both Mental Health Awareness Month and Asian Pacific Islander Heritage Month. But as we move into summer, remember that our wellbeing as dancers of color is something to prioritize all year round.

As a chunky Asian baby in a leotard, I had no idea yet how precious or valuable I was when I started in ballet. Instead, I only saw that I was clearly not cut from the same cloth as elegant princesses and swans whose dancing I admired. The chance to don yellowface in the Chinese variation during "The Nutcracker," or to be a kowtowing, shuffling child in "The King and I" in the school play felt like places I was welcome to exist—to shine—as a child who dreamed of being onstage.

Many years later, I see that I deserved so much more than to beg for scraps in the form of sidekicks and ethnic stereotypes. Black, Indigenous, and all People of Color deserve so much more. We need not silence the parts of us that are “too much” for white norms, be it too ethnic, too dark, too curvy, too loud. White people do not own dance—not even ballet. As former Dance Theater of Harlem ballerina Theresa Ruth Howard taught me, these precious art forms belong to all of us, as well.

Now, at the end of Mental Health Awareness Month and Asian Pacific Islander Heritage Month, remember that prioritizing our mental health—our wholeness, joy, and humanity are year-round activities. Every month is for our “history” or our “heritage.” With that in mind, I bring you five personal reflections on what it means to care for ourselves mentally and emotionally as People of Color in dance. Hear from Christopher Montoya (formerly of Ballet Trockadero, Dance Fremont Managing Director), Dr. Sue Ann Huang (co-director of The Tint Dance Festival), Alicia Allen (former dancer with Janet Jackson, Mary J. Blige, and Shakira to name a few), Robert Moore (formerly of Spectrum Dance Theater), and Vivian Little (retired ballerina and Dance Fremont founder).

Photo courtesy of Christopher Montoya

Find an environment where you can thrive

For Christopher Montoya (he/they), not having the right body type was a stressor that only compounded on top of being brown, gay, and working-class. Eventually, Montoya discovered their truth as being gender-non-conforming, and would often feel pressure to pass as straight in order to be hired for dance jobs. Finding an encouraging ballet teacher who embraced Montoya’s authentic self, and then discovering a community in Ballet Trockadero were defining moments.

“Going into Trockadero is really where I found myself,” Montoya said. “The dancers were Australian, Venezuelan, Spanish, Mexican, Black, Asian. We all felt like misfits because we didn’t fit into this binary mold of ballet. Trying to pass as a straight man always felt so fake and defeating. But here, I got to be me.”

From Montoya’s experience, taking time to situate oneself in a supportive dance environment is crucial. (For some, this could mean choosing a Black-led dance school or a class taught by a teacher of color). If the environment is unsupportive, it could be time to leave or look elsewhere.

Sue Ann Huang and Arlene Martin. Joseph Lambert photo

Divest from that which does not serve you

Dr. Sue Ann Huang (she/her) not only co-founded an event centering BIPOC, Tint Dance Festival, her dissertation focused on choreographers of color in the Pacific Northwest. Most recently, she’s been thinking deeply about what liberation is possible through concert dance, which still possesses an intimate, even symbiotic relationship, with white supremacy.

While white supremacy once referred to overt hate as seen through groups such as the KKK, white supremacy today refers to an ideology that acts in both overt and subtle or unspoken ways. In western society, for example, white culture, white norms, and white people are valued more highly, and above other cultures. A cursory glance at the majority of ballet and modern dance companies show this favoring of whiteness, as seen through artistic leaders, company rosters, and choreographers whose work is presented.

In Huang’s view, dancers of color must strive to create space between what’s true and what’s cultural default. Today she does this by resisting the pressure to see certain “it” choreographers or companies, and instead asks herself what will bring joy.

“What kind of dance do I visually want to see? What kind of movement do I want to do? I am mostly only seeing shows produced by People of Color I care about, and that’s OK.”

Alicia Allen, photo courtesy of the artist

Hold them accountable

As a Black woman in a predominantly white dance department, Alicia Allen (she/her) felt invisible. From the professor who asked if she was in the right place, to the bathrooms littered with posters of white dancers, and how-to instructions for the perfect ballet bun, the message was subtle, but loud:

“My Blackness and street styles did not ‘make’ the walls.”

It wasn’t until Allen connected with other students who had experienced similar events that she gained the courage to fight. During her senior year, the majority of her efforts were focused on holding her dance department accountable. She served on committees, planned town-hall events, and lobbied to get a racist class canceled. And she’d do it again in a heartbeat.

“Don’t be afraid to speak your truth and share your experiences. You should always hold your teachers and professors accountable for your education. Hold them accountable for respecting dance cultures and communities.”

When Allen teaches hip-hop today, she never skips over the fact that this dance style was birthed from the joy and pain of Black people. Instead, she encourages her students to face their own discomfort as they reckon with history—a necessary part of respecting where the art comes from.

Roberty Moore jumps; Tracey Wong photo

Reorient your organization toward justice

In the past, Robert Moore (he/they) has seen dance organizations think that anti-Blackness, the increase in Asian American attacks, or what it means to live on occupied Coast Salish land, are not relevant to ballet or modern dance. But Moore does not stop being Black when he comes into the studio.

“What puts a nice little grin on my face is seeing organizations step up for the first time, seeing them stumbling over themselves, and actually learn something from pulling some weight, rather than just being passive,” he said.

Moore has found rest this past year by being in community with other Black artists: getting to discuss life—including topics that have nothing to do with race—has brought them joy.

Remember, Moore said, People of Color do not owe anyone a conversation or explanation about race, ever: “Honor the quiet revolution of a dancer of color just going to class, rehearsing, and taking moments to exist freely.”

Re-think ballet and dance education

Vivian Little (she/her) never connected race to body type when she was dancing with Pacific Northwest Ballet and San Francisco Ballet in the 1980s. Years later, she was teaching at a university and her colleagues of color recounted the discrimination that they had faced. Only then was she able to connect the dots between racism and the “defectiveness” of certain bodies. Through this lens, the concerns of her colleagues made sense: a Filipina whose short legs prevented her from earning short-tutu roles, a Columbian danseur with who never had the right “look” for a prince. Being of Irish and Japanese ancestry, Little thought about how she herself was often cast as the sensual or Latina role because of her “exotic look.”

Today, Little pushes back on the uniformity and preferred Eurocentric ballet aesthetics. One way to do this has been learning more about the human body and movement mechanics related to ballet technique. Little sees the potential in every student, whether their first position is a delicious little slice, or a whole half, of pie; whether their leg reaches up toward the heavens in arabesque, or points down toward the earth; whether they look like generations of European ballerinas, or they are helping to illuminate the multifaceted, multicultural beauty alive in ballet.

“Ballet teachers must teach to the person, not to an ideal,” Little said. “It takes much more thought, care and intentionality to be inclusive because of the waters of white supremacy we've been swimming in and the air of racism we've breathed for centuries.”

Photo courtesy of Vivian Little

Resources

Additionally, please check out the work of the following Seattle-based artists: Alicia Mulikin, Dani Tirell, Noelle Price, Randy Ford, Imana Gunawan, Cheryl Delostrinos, Amanda Morgan, Sarah-Gabrielle Ryan, Donald Byrd/Spectrum Dance Theater, among many, many others.

Mental Health and the Importance of Cultural Competency

From as early as I can remember I wanted to move. I felt a connection to music and energy through the floor that I couldn’t explain. When I look back on the things that shaped me, dance has been a constant. Through dance I found a voice and a method of expression that I couldn’t recreate

By Maddie Walker

Madison Walker started her dance journey at a young age. Growing up in New Orleans as a young mixed woman, she always felt a deep emotional connection to dance that allowed her to express who she was. At 12 years old she was selected to be a part of a small ballet conservatory, JPB Le Petit Ballet (now Northwest School of Dance), where she learned to utilize the backbone of classical technique. For many years Madison studied the Vaganova technique of ballet under Jennifer Picart Branner. Madison studied abroad in the beautiful country of Norway where she danced with Extend, a small dance company.

Since high school, Madison has danced and taught throughout the Pacific Northwest, currently acting as the Assistant Artistic Director of Academy of Dance Port Orchard. In addition to teaching and choreographing, Madison spent the 2019-20 season dancing with PRICEarts N.E.W. as a company member.

Her passions include traveling the world and working as a Certified Peer Counselor by day. Mental health is an educational passion and personal passion for Madison and has led her to serve on a board of directors for United Peers of Washington where she has been able to find avenues to blend her work in art and mental health.

Click Below to Shop the Look:

“Be Nice” Crew by Sunday Outfitters | K-Warmer by Apolla Performance | Metallic Warm Up Booties by Bloch

From as early as I can remember I wanted to move. I felt a connection to music and energy through the floor that I couldn’t explain. When I look back on the things that shaped me, dance has been a constant. Through dance I found a voice and a method of expression that I couldn’t recreate through speaking. Growing up in New Orleans, I had an early appreciation for art and flare as a means of communication. The culture of New Orleans is vibrant― from cajun food to Mardi Gras. When I was young, I rode in parades on giant floats made of papier-mâché and watched as dancers did their choreography to live marching bands down the street; inspiring me with every step.

At the age of 4, my father and biological mother separated. For 6 years I was under the primary care of my biological mother who unfortunately, was living with an active addiction. In the time I lived with my biological mother, I experienced trauma, neglect, and abuse. I found my escape in being able to dance, being able to create with my body, and feeling a physical release through creative movement. At the age of 10 my father married my step-mom who I refer to as my Mom. My mom has been an integral part of me learning to love myself and how to be loved.

At the age of 10, my mom, dad, sister, and I moved to Gig Harbor, Washington after our family had been displaced due to Hurricane Katrina. When I moved to Washington I struggled in a different way. The environment I had lived in before was far different from the suburb neighborhoods that I moved to. I felt isolated because of my culture, my skin tone, and the kinks in my hair, but also because I felt broken amongst what seemed like perfect families. Growing up as a mixed woman I often felt out of place, and still struggle at times to feel I belong in certain spaces. Coupled with my trauma, I often found I didn’t identify with many of my peers.

Click Below to Shop the Look:

Lola Forest Leo by Elevé Dancewear | Mesh Socks by Elevé Dancewear

The reality of being a woman and person of color or a member of a marginalized community is that mental health is often not seen from our perspective. Part of my drive to work in mental health is to be the representation I did not have in my community. I often felt like I did not have the space to talk about certain topics and that my feelings were offensive to others. Even while writing this, I find myself looking for “polite” ways to say I dealt with racial trauma and felt awkward talking to anyone for fear of offending white people.

Being a woman of color who provides mental health services to peers of color means I can identify and relate to their unique version of recovery. Through my work as a Peer Counselor and board member of United Peers of Washington, I am able to advocate passionately for the importance of cultural competency and tolerance. I personally struggled internally for a long time because I came from a background where people go through hard things; this was not “trauma”, this was life. Accepting that bad things don’t have to happen to you is a journey all on its own.

Accepting that it is okay to feel and to be hurt is another hurdle, a hurdle that for many people of color can mean being perceived as weak when society expects us to be strong. For a long time, I thought that acknowledging and talking about my trauma was shameful; but in time I learned that confronting your barriers and growing takes far more strength.

My daily goal is to act as a support to all who feel lost or alone, but especially to communities of marginalized people. Normalizing the feelings of trauma and how we process things is a monumental first step. Allowing ourselves to find outlets and coping mechanisms is the next.

Through sharing my story, my work, and art, I hope to show others that they are not alone and that there is power in your individual and unique story. Today, I recognize and celebrate that my experiences are my superpower. My ability to identify with diverse communities is invaluable, and my past does not define me: I do. But most of all? I found my therapeutic outlet through the dance floor.

“Something about being able to dance has always allowed me to feel a sense of belonging; even if for just the moments I was moving.”

Something about being able to dance has always allowed me to feel a sense of belonging; even if for just the moments I was moving. My parents bent over backwards to allow me to dance when we moved to Washington. I remember driving an hour one way to go to class and sitting in traffic while doing my homework. What I don’t think my parents ever realized is that they saved my life by allowing me to have that outlet. I was able to find myself through creative expression and that is a gift I want to share with the world in every way I can―especially through my work as a peer counselor.

For those of you reading who may not know what a “peer” is in the context of mental health, it is anyone who shares lived experience and makes an effort to share their lived experience in a way that will inspire others to find their own path. Amazing humans all over the world work as peer counselors; but more importantly, there are grassroots organizations and groups in every region of Washington State consisting of peers who offer support to their communities.

Click Below to Shop the Look:

I am always working on ways to merge my peer work with my art and one way I hope to do that is by providing psychoeducation to communities through the art of peers in my community. Throughout my journey of recovery―from depression to living with anxiety―I have learned that recovery is not linear, and expression is imperative. Finding my community and bridging art and my work has been one of the greatest joys in my life and has inspired me to realize my fullest potential. I encourage you to find your community and to discover your inspiration.

For more information on United Peers of Washington and other Peer related resources, check out the UP of WA Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/UPofWA

Karl Watson on Finding Balance and Seeking Transparency

As dancers, we’re encouraged to push ourselves as far as we can, often until our breaking point. Finding the harmony between challenging ourselves and staying within our boundaries can be a tough balancing act. Karl Watson of Whim W’him gives insight into this challenge, his dance journey, and what he hopes to see moving forward in the dance industry.

By Madison Huizinga, DWC Blog Editor

Photos: Stefano Altamura & Bamberg Fine Art Courtesy of whimwhim.org

As dancers, we’re encouraged to push ourselves as far as we can, often until our breaking point. Finding the harmony between challenging ourselves and staying within our boundaries can be a tough balancing act. Karl Watson of Whim W’him gives insight into this challenge, his dance journey, and what he hopes to see moving forward in the dance industry.

Karl first fell in love with dance because his mom took him to see A Christmas Carol around the holiday season. “I freaked out within the first 10 minutes,” Karl laughs. His mom took him out of the theater and into the lobby of Playhouse Square in Cleveland, Ohio. She asked the employees if any other shows were happening that night, and they suggested she take her son to see The Nutcracker. As soon as he set his eyes on the show, Karl was mesmerized. Eager to learn dance himself, his mother enrolled him in a creative movement class. He continued dancing at The School of Cleveland Ballet, later floating between a couple of different studios. Karl later got more involved with competition dance, falling in love with jazz and musical theatre.

Towards the end of high school, Karl realized he wanted to pursue a career in dance and thus wanted as much training as possible. He soon began dancing seven days a week with a focus on ballet, jazz, and musical theatre. Around the time when Karl began his freshman year at Butler University, YouTube began taking off. He recalls coming across videos about Crystal Pite, as well as William Forsythe’s improvisation techniques. These online resources and the resources on his campus opened him to the range of dance that was happening outside his bubble.

During his time in college, Karl did two summer intensives summer intensive with Hubbard Street Dance in Chicago and a winter workshop with Doug Varone. At Butler, he also got the chance to take master classes from Gustavo Ramírez Sansano who was the artistic director of Luna Negra Dance Theater at the time. After graduating, Karl ended up landing an apprenticeship with Luna Negra and moved to Chicago. Karl ended up becoming a performing apprentice and toured with the company before it folded in 2013. He ended up staying in Chicago and performing with Visceral Dance Chicago as a founding member. Later on, while in New York, Karl ended up auditioning for Whim W’Him, as they were having a workshop and audition over there. He got the job with Whim W’Him in 2016 and relocated to Seattle where he’s been ever since.

Ever since Karl discovered dance, it’s been his most effective tool for self-expression and storytelling. He shares that as a child, he was fairly quiet. “I was the kid who liked to sit at the grown-up table and just listen...I was just a little more internal,” he says. Thus, he loves that dance can be a “very internal practice,” allowing him to be within his body and self-discover.

However, nowadays, Karl shares that he is most moved by experiences that take him out of his body and allow him to connect with his own or other people’s physicalities. “I think it’s just the physicality of [dance] in a world that feels increasingly less physical,” Karl says of what draws him to dance. He loves how qualitative the art form is, the meanings of dances are up for interpretation, making it even more compelling for audiences to watch. Karl also marvels at how technology and social media have given dancers new platforms to gain traction and share their work with the world.

While classical ballet training has been invaluable for his training, Karl shares that dance challenges he’s faced have come from the ballet world, specifically from ballet’s strict physical standards, as well as imposter syndrome. Karl is interested in the “decolonization of contemporary dance,” involving the decentering of European or Western standards. He’s eager to see different dance approaches being utilized, specifically those that center on the individualities of dancers through standardized modes of training. For too long, creating, training, and rehearsing has involved fitting his body into a rigidly pre-determined shape. Now, Karl feels as though he can pull movement out of his body in a way that challenges him but also works within the bounds of what’s possible for him. “I think it’s just about being in your body and finding what your body can do,” he says.

In the dance world, Karl hopes to see more transparency within dance education and more productive discussion about personal development and the realities of being a working dancer. While pre-professional and BFA programs have a multitude of benefits, Karl points out that they can be quite insular. Having holistic opportunities for networking outside of institutions would be helpful for dancers’ careers.

In terms of professional companies, Karl wishes to see more transparency and equity across the dancing hiring process. For example, he shares that the Dance Artists’ National Collective is furthering this agenda by “advocating for safe, equitable, and sustainable working conditions for dancers in the U.S,” as a way to empower dancers who are often underpaid and mistreated within the industry.

While Whim W’him is on its break, Karl is working on an outside project with the choreographer Emily Schoen Branch and fellow Whim W’Him member Liane Aung. The group is planning on making a dance film and hopefully performing at festivals later this season when more in-person events begin happening. He is also teaching in-person Dance Church classes in Seattle. Whim W’him released two new dance films with Mark Caserta and Rena Butler, available for viewing online. Stay tuned as Karl and the rest of Whim W’him continue phasing back into in-person performances this winter after a long-awaited break.

Interested in writing for the DWC Blog? Click below to fill out the DWC Contributor application!